Researchers found that blocking dopamine receptors in male mouse brains dampened their preference for females

Male mice are allured by scent, particularly by behavior-changing chemical signals called pheromones that are released by females. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have now discovered how a pheromone-processing mechanism in the brain determines the sexual preference of male mice, motivating them to prefer females over males.

Earlier studies in the lab of Prof. Tali Kimchi in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Neurobiology Department had focused on the link between sexual preference in mice and the vomeronasal organ, or VNO: a scent-sensing system that, unlike the nose, mainly responds to pheromones. The VNO has lost its function in humans, but it plays a role in directing the behavior of numerous animals. Kimchi’s team had shown that genetically engineered male mice lacking a functioning VNO showed no aggression toward other males and were equally interested in mating with males and females. It’s not that these engineered mice were unable to distinguish between the sexes: When the researchers exposed them to negative conditioning against female pheromones, these mice began to avoid mating with females but continued to display sexual behavior toward males. These findings suggested that without the pheromone signals processed by the VNO, the male mice could easily lose interest in females.

Dopamine, sexual preference and aggression

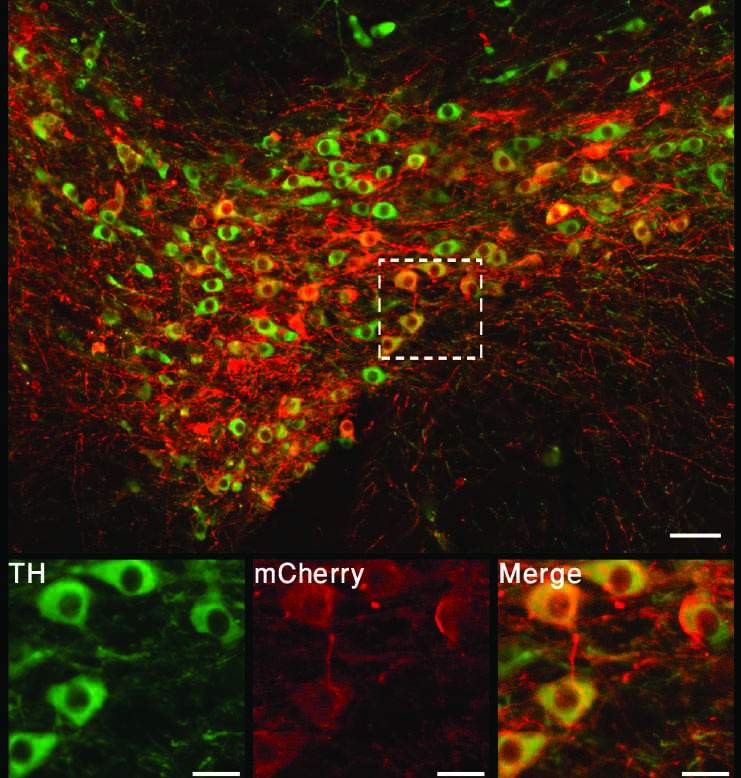

In the study published in Cell Reports, Dr. Yamit Beny-Shefer, then a doctoral student, and other members of Kimchi’s team revealed the neural circuit responsible for the sexual preference of male mice. They showed that the female pheromones activate a reward mechanism: This mechanism begins with the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which in turn stimulates a “pleasure center” – the neuronal cluster called nucleus accumbens. In the absence of this stimulus, the males showed no preference for females.

In one set of experiments, the researchers let a female mouse into a cage housing a male – either a regular male or one genetically-engineered to lack a VNO. Dopamine levels rose sharply in the brains of regular males but not in the brains of engineered mice. The behavior of the two groups of males differed accordingly: Regular mice exhibited sexual behavior toward females and aggression toward males; the engineered mice, on the other hand, showed almost no aggression toward males and were equally sexual toward males and females.

Next, the researchers managed to recreate a preference for females in the engineered mice by manipulating the pleasure center in their brains. They employed optogenetics, a method that makes it possible to activate or neutralize certain neurons with great precision by exposing them to a microscopic light beam. By doing so, the scientists were able to bypass the pheromone-processing mechanism lacking in these mice, directly simulating the effects of dopamine in their “pleasure center.” As the male mice underwent this stimulation, they were placed in close proximity to females so that the reward mechanism was activated just when females were around, creating a conditioning of sorts. Following the conditioning, these mice showed a marked sexual preference for females, similar to that of regular mice, although they retained a certain level of sexual interest in some males and their behavior toward other males remained non-violent.

Ultimately essential for survival

After establishing the connection between activation of the “pleasure center” and sexual preference, the researchers investigated this neuronal circuit in greater detail. They injected into the brains of non-engineered mice a molecule that blocks particular dopamine receptors in the brain. Blocking this specific neuronal circuit eliminated the sexual preference of the males toward females. Even some two weeks after the blockage, these mice still showed no preference for females.

Explains team member Dr. Noga Zilkha: “It’s been known that sexual stimuli activate the brain’s reward system – that’s not news. What’s new in our findings is that the activation of a certain reward mechanism plays a critical role in determining the sexual preference of male mice for females – a preference that’s essential for reproduction and ultimately, for the survival of the species.”

The team also included Dr. Yael Lavi-Avnon, Nadav Bezalel and Dr. Molly Dayan of the Neurobiology Department, and Drs. Ilana Rogachev and Alexander Brandis of the Life Sciences Core Facilities Department.

Prof. Tali Kimchi’s research is supported by the Joan and Jonathan Birnbach Family Laboratory; and the Ethel and Harry Reckson Foundation.

Recent Comments