Matching drugs to tumors may lead to personalized treatment and new therapies

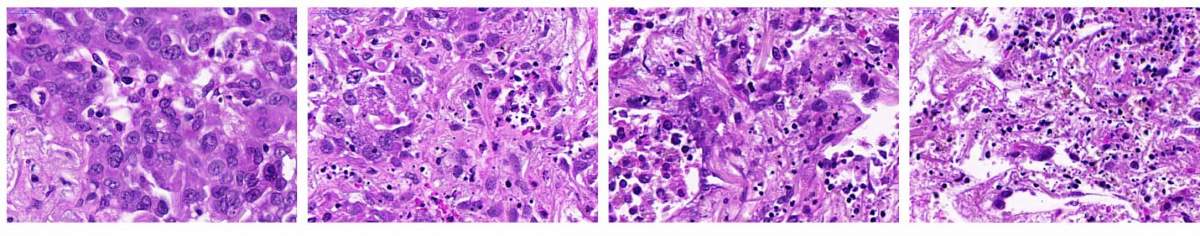

Lung cancer samples: Far left untreated. Lung cancer tissue failed to respond when exposed to a microtubule inhibitor drug (left) or to a drug that enhanced the apoptosis-inducing pathway (middle). But when the two drugs were applied together to the same tissue, the cancer cells died (right)

Choosing the right drug for each cancer patient is key to successful treatment, but currently physicians have few reliable pointers to guide them in designing treatment protocols. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science and Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have now developed a new method for selecting the best drug therapy for a given tumor based on assigning scores to the cells’ internal messaging activities. In addition to helping physicians choose from a list of existing treatments, the method can help identify new molecular targets for the development of future drugs. In fact, the researchers have already used it to single out a gene that can be targeted for effectively treating breast cancers with a BRCA mutation. The study was recently published in Nature Communications.

The most common molecular way of matching drugs to a tumor is to look for particular mutations in the tumor’s cells. Unfortunately, the presence of such mutations is no guarantee a drug will work, and, in any event, many drugs are not aimed at mutations to begin with. There have also been attempts to predict a drug’s effectiveness by analyzing the expression of certain genes in a tumor, but the expression level of very few genes have been shown to be helpful in guiding physicians in making treatment decisions.

In the new study, two labs – one headed by Dr. Ravid Straussman of Weizmann’s Molecular Cell Biology Department, the other by Prof. Gad Getz of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts – joined forces to develop a more effective approach, basing their study on the enormous datasets on cancer that have become available in the past few years. This approach does not rely on mutations or on individual genes, but rather on signaling pathways: chains of biochemical signals that convey crucial cellular messages, for example, whether a cell should divide or grow, or in what way its metabolism should be altered. Numerous genes are expressed in the cell in order to transmit the message in each pathway, so sophisticated methods are needed to uncover the activity in these chains.

Postdoctoral fellow Dr. Rotem Ben-Hamo analyzed vast international datasets containing information on the expression of all genes in some 460 cancer cell lines – that is, different models of cancer – from ten different cancer types. Using an advanced bioinformatics tool, PathOlogist, developed by Prof. Sol Efroni of Bar-Ilan University, the researchers assigned to each pathway an activity score, which takes into account not only gene expression levels but also prior knowledge about the structure of each pathway, the interactions of the genes within it, and whether a given gene blocks or stimulates the pathway’s message. The scientists then correlated these scores with datasets containing information on the sensitivity of different cancer cells to nearly 500 different anti-cancer drugs.

They found that the activity scores of some of the pathways enabled them to predict whether a specific cancer would be sensitive to a particular drug. In other words, the researchers created a profile for the cancerous tissue that could direct clinicians to the best drugs for eradicating the tumor. Overall, they were able to make such predictions for more than 30 existing drugs. For example, when certain lung cancer cells had a high score for a pathway triggering apoptosis, a form of cell suicide, these cells were likely to be killed by a class of drugs known as microtubule inhibitors.

The researchers created a profile for the cancerous tissue that could direct clinicians to the best drugs for eradicating the tumor

Next, the scientists showed that they could use the pathway knowledge not only to predict but to alter the cells’ response to a drug. They obtained from one patient lung cancer tissue in which, according to their analysis, the apoptosis-triggering pathway was not particularly active. In test tube experiments this lung cancer tissue, as expected, was resistant to microtubule inhibitor drugs. But when, in addition to microtubule inhibitors, the researchers simultaneously applied a substance that increased the activity in the apoptosis pathway, these drugs effectively killed the cancer cells.

In further analysis of the datasets, the researchers correlated the activity scores of signaling pathways with yet another type of information: which genes play such an essential role in various tumors that silencing, or blocking these genes can kill the tumor. They found that here too, the pathway scores helped them identify such “sensitive” genes in a variety of tumors. For example, they found that breast tumors with specific activity in the BRCA pathway – which correlated with the presence of a BRCA mutation – were extremely dependent on the activity of a gene called MAD2L1. The bioinformatics analysis predicted that silencing this gene can result in the death of tumor cells in patients with a BRCA mutation. This prediction can serve as a starting point in the search for new or existing drugs to treat this devastating breast cancer.

Overall, the study’s findings suggest that signaling pathways can serve as predictive biological markers in personalized medicine of the future, helping physicians tell in advance which patients will best respond to which drug. Moreover, the pathways can help researchers identify the Achilles heel of various tumors to which drug development can be directed.

Study participants included Dr. Adi Jacob Berger, Dr. Nancy Gavert and Dr. Yaara Zwang of the Straussman lab in Weizmann’s Molecular Cell Biology Department; Dr. Mendy Miller of the Getz lab at the Broad Institute; Dr. Guy Pines of Kaplan Medical Center; Dr. Roni Oren of Weizmann’s Veterinary Resources Department; Prof. Eli Pikarsky and Dr. Tzahi Neuman of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; and Prof. Cyril H. Benes of Massachusetts General Hospital.

Recent Comments