Analyzing a handful of charred seeds reveals the ancient builder of an iconic structure in the Western Wall Tunnels

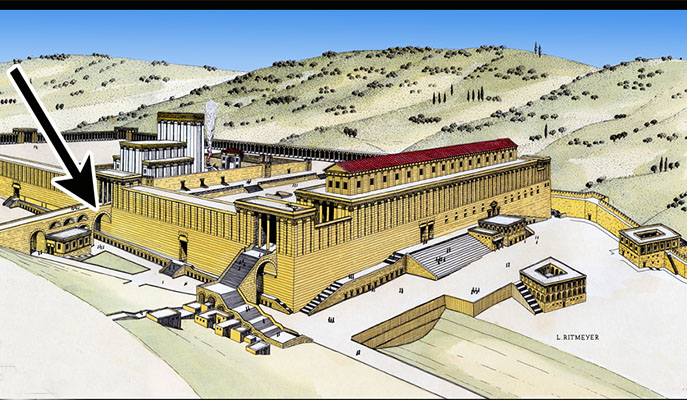

Wilson’s Arch is still partially visible today to visitors to the Western Wall in Jerusalem

Who built Wilson’s Arch? It wasn’t Charles Wilson, a British ordinance surveyor in and around Jerusalem toward the end of the 19th century. The arch, partially visible to all visitors to the Western Wall, has been a prominent fixture in Jerusalem’s landscape for centuries. Some have thought it was originally constructed around the turn of the common era by the Roman king Herod – one of the great builders of history – but others had assigned it a later date, believing it was erected in the Early Islamic Period, some 600 years later.

Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto and Dr. Johanna Regev of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Scientific Archaeology Unit spearheaded the chronological research of a recent archaeological excavation conducted with the expressed aim of solving the Wilson’s Arch riddle. The excavation, located in the Western Wall Tunnels, was led by archaeologist Dr. Joe Uziel, Tehillah Liebermann and Dr. Avi Solomon, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and undertaken by the Western Wall Heritage Foundation as part of the tourist development of the site.

The Weizmann Institute researchers have been perfecting methods of “micro-archaeology” to characterize the layered deposits and to then determine the connection between any sample that is dated and the archaeological event to be dated, in great detail. “For this project we had to develop a very specific strategy, starting by being in the excavation, itself,” explains Boaretto.

Excavations undertaken by the Israel Antiquities Authority took place in the tunnels under the wall

Prof. Boaretto explains that conducting archaeological research on urban structures like Wilson’s Arch, and in particular determining its age, is much more complicated than in almost any other archaeological setting. In an urban center that is still occupied over 2000 years later, the structures might be used for centuries, components may have been reused, parts of the structure torn down and rebuilt, and the stones, themselves, keep their secrets close. Absolute dating of architectural structures, as opposed to relative dating based on pottery and coins, is particularly important to correlate with existing texts and with historical figures. It is little wonder then that the history of Wilson’s Arch has remained elusive.

One of the key materials the group sought in Wilson’s Arch was remains of the mortar or cement used between the stones. This material was produced at high temperatures and aggregates were added to acquire desired properties; thus, charred seeds can sometimes be found embedded in the plaster. So the first challenge was to determine whether the charred material was indeed a constituent of the original plaster, and the next challenge was to determine if this plaster was part of the original construction or a later repair. Any seeds found under the bases of the large structures could also be dated and the dates of the seeds assumed to be older than the construction. Every date obtained was thus the result of a mini-research project. Back in the D-REAMS (Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometer) lab in the Weizmann Institute of Science, Boaretto and her team analyzed the plaster and the charred materials they removed from the dig site to study their composition and crystallinity and from there, to determine their age.

It is little wonder then that the history of Wilson’s Arch has remained elusive

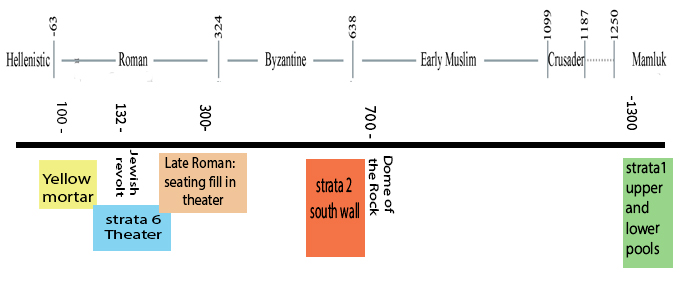

Seeds found between the large boulders of the arch returned dates prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during the period where Jerusalem was governed directly by the Roman Procurators, the most famous of which is Pontius Pilate.

According to Dr. Uziel of the Israel Antiquities Authority, “This comprehensive dating of the micro-remains provided an unequivocal solution to a lengthy archaeological riddle – the riddle of the date of Wilson’s Arch.” The arch was part of a bridge which led worshippers to the Temple Mount and was built as part of the Western Wall of the compound some 2000 years ago. Through this joint research project, we were able to determine that the arch, which supported one of the main pathways to the Second Jewish Temple, was built in two distinct stages. In its early days, during the rule of King Herod the Great or slightly afterwards, the bridge was 7.5 meters wide. Just a short time later, in the first century CE, the width of the bridge was doubled, reaching a width of 15 meters. “The size and workmanship of the arch attest to the importance of the Temple Mount during the days of the Second Jewish Temple, when thousands of people would have taken part in the ceremonies, particularly during holidays,” he adds.

Straw and other botanical remains in the plaster of Wilson’s Arch that have been radiocarbon dated. Scale indicates mm

The archaeological team also worked on dating another piece of Jerusalem’s history — a small theater-like structure constructed beneath Wilson’s Arch. The radiocarbon dating indicates that the theater’s construction was most likely initiated just before a historically significant date — the outbreak of the Second Jewish Revolt in 132 AD, often known as the Bar Kochva revolt – and not later than Hadrian’s death. Ultimately, the group dated 33 samples from many different locations, covering a period of over 1000 years.

“The Wilson’s Arch riddle could not have been solved without the use of micro-archaeology,” says Boaretto. “We showed that the extreme accuracy of our lab results, even for the tiniest of samples, can resolve these issues with a high degree of certainty, and we think they might help solve other archaeological puzzles for which radiocarbon dating had not previously been considered to be sufficiently precise.”

“From an arch built by Herod, to a theater complex abandoned before it was completed as a consequence of Bar Kochba revolt, you can take a fresh look at the city’s history and place this monumental building in its proper historical setting. That certainly helps solve this riddle,” she says.

The project is a joint undertaking, funded by the Israel Science Foundation, aimed at dating the various remains and settlements in ancient Jerusalem. It is based on a collaboration of field archaeologists Prof. Yuval Gadot (Tel Aviv University), Dr. Joe Uziel and Dr. Doron Ben-Ami (IAA), together with Boaretto and Regev, who applied the overall dating strategy developed at the Weizmann Institute in the field and in the D-REAMS lab.

Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto’s research is Head of the Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science; her research is supported by the Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory; and Dana and Yossie Hollander. Prof. Boaretto is the incumbent of the Dangoor Chair of Archaeological Sciences.

Recent Comments